Dispute Over Texas History : A long-standing disagreement about teaching Texas history in schools has been resolved. The TSHA was central to the year-long debate on the board of directors. Association rules require a balance between academics and non-academics, with the president having the final say in case of a tie. The TSHA board had 12 scientists and eight non-academic members in the past three years.

J.P. Bryan, the group’s executive director and a retired oilman, said this piece altered TSHA’s ideology by having academics criticize Texan heroes. Bryan thought this piece changed TSHA’s perspective. Bryan’s critics said he didn’t sufficiently credit non-Anglo communities’ role in Texas’s past. TSHA’s top historian, Walter Buenger, countered Bryan’s claim that the board was unfair by noting that previous non-academic presidents had doctorates, written books, and taught as adjuncts without objections.

Bryan sued the company in May, claiming rule violations in the board composition and an attempt by President Nancy Baker Jones to remove him. Jones and Secretary Cole both quit after a mediation meeting. Two non-academic individuals will join, and a third seat will be filled by another non-academic person. Bryan withdrew his lawsuit, ending any chance of a trial. Bryan said the settlement wasn’t about pride but aligned with TSHA’s original goal. He said it multiple times.

Also Read : Transgender Membership Lawsuit Dismissed: Judge Upholds Kappa Kappa Gamma Decision

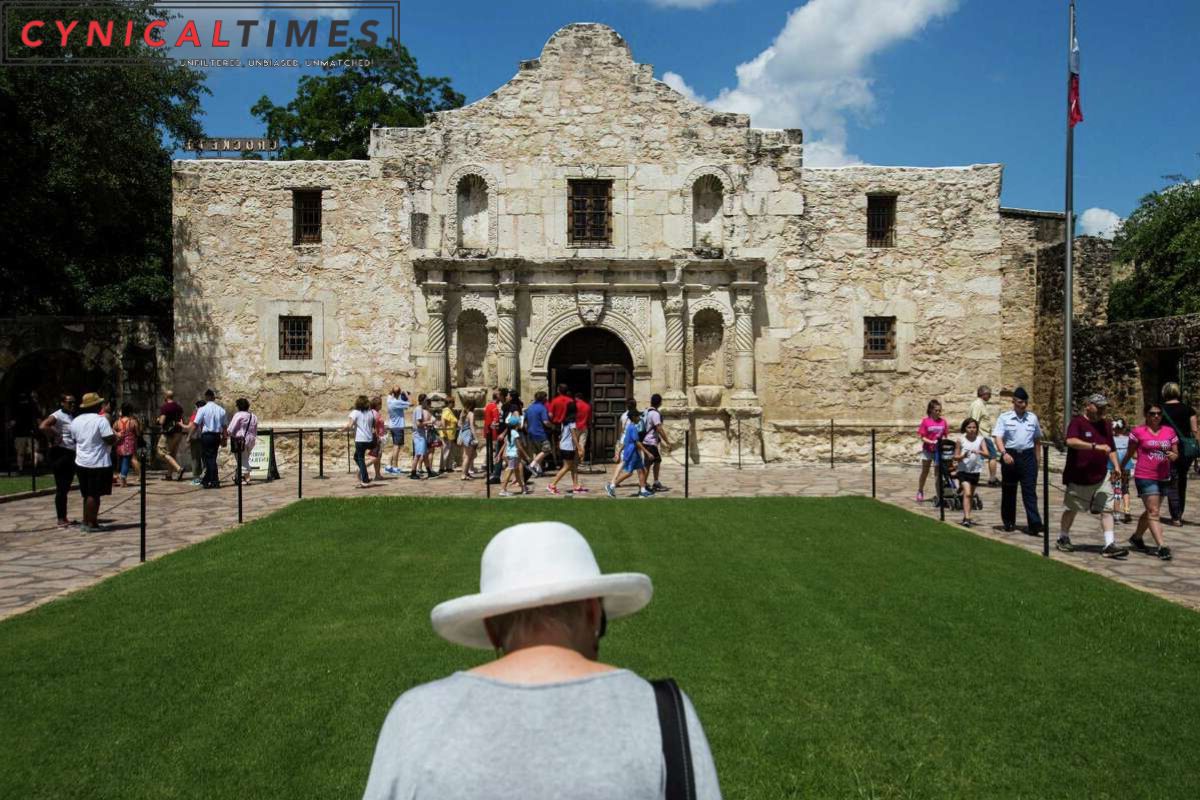

Bryan plans to nominate three people for the board of directors. “I’m confident we’ll find qualified people this week,” he said. Next week, we’ll have something for board approval. The TSHA was founded in 1897. Its role is to create research materials and educational programs about Texas. The Southwestern Historical Quarterly, Texas Almanac, and Handbook of Texas are important TSHA publications. Teachers, authors, and institutions often use these materials to shape the information shown at historic places in Texas, like museums, Spanish missions, and battlefields. The Texas Legislature funds the group, and its books greatly influence the teaching and interpreting of the state’s history in public schools.

As the debate nears resolution and the board approaches balance, it’s a turning point for the Texas State Historical Association and its role in teaching Texas history.

Our Reader’s Queries

What was the dispute over Texas?

The Mexican-American War was a conflict between the United States and Mexico that took place from April 1846 to February 1848. The war was sparked by the United States’ annexation of Texas in 1845 and a disagreement over the boundary of Texas. Mexico claimed that the boundary ended at the Nueces River, while the United States claimed it was the Rio Grande. This dispute ultimately led to the outbreak of war.

When was there a dispute over Texas land?

From 1845 to 1848, the United States went through a series of events that would shape its history forever. The Annexation of Texas, the Mexican-American War, and the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo were all significant milestones during this period. These events marked the expansion of the United States into new territories and the acquisition of new land. The Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo, in particular, was a crucial agreement that ended the war and established the Rio Grande as the border between the United States and Mexico. These events had a profound impact on the political and social landscape of the United States and continue to shape its identity today.

What was the boundary dispute over Texas?

In 1845, the United States took over Texas and then got into a disagreement with Mexico about the border between southern Texas and Mexico. Texas said that the border went all the way to the Rio Grande, but Mexico said it was the Nueces River, which is 100 miles (160 kilometers) to the east.

What was the main dispute Mexico and the US had concerning Texas?

The border between Texas and Mexico was a point of contention, as the Republic of Texas and the U.S. believed it to be the Rio Grande, while Mexico argued it was the Nueces River further north.